Episode 3Disregard Short-Term Forecasts

Forecasts from market prognosticators have no predictive value. Don’t let them influence your decisions. Stay focused on your investment plan.

Share this Video

Transcript

| Chris Davis | 00:00 | Well, one of the struggles that I've had in this profession for 30 years is, every cocktail party, somebody wants a forecast. And if you go and speak at a conference with financial advisors, they always have a strategist, an economist; they're going to opine about inflation, they're going to opine about interest rates market forecasts. And when you look at the data, these forecasts have no predictive value, yet they're all making a living. What's worse, people are reacting to it. I'm curious what you think about why that phenomena exists, how it plays out in terms of the investor psyche, and whether there is a defense against the dark arts that could help people be less sensitive to this sort of desire. |

| Morgan Housel | 00:50 | Here's my nuance on it. Not to push back a little bit, but I think people are actually very good at forecasting the economy, except for the surprises, and the surprises are all that matter. That's really the nuance of this. It's not that we can't predict, that we can't predict surprises and nothing else matters about the surprises. The Economist magazine that I greatly admire, I think it's one of the best publications out there, every January they put forth an edition that looks at the year ahead. They're going to survey and forecast the next 12 months. In January of 2020, their edition did not say a single word about COVID because it wasn't known back then. In January of this year, 2022, there was not a single word about Russia/Ukraine because it was not known back then. It's not a criticism against the editors of the Economist. It's just in any given year, the biggest risk is what nobody sees coming. |

| 01:39 | There's a financial advisor who I really admire named Carl Richards and he says, risk is what is left over when you think you've thought of everything. I think that's the best definition of risk. This is why the forecast persists despite the track record because there are a lot of things that we can forecast with some sense of like, "Oh, given the data and given what we know about history, this is what's likely to play out, except the surprises." When you live in a world where I can guarantee you the biggest news story in the next 12 months is something that you and I or anyone else is not talking about because it's always been like that. | |

| 02:11 | If you look back historically, the things that are in the news, economically, things like earnings forecasts, budget deficits, and elections. It's not that those things are not risky. It's that they're not surprises. They're written about all day. People know that they're going to come. You don't know who's going to win the election, but you know there's going to be an election. | |

| 02:30 | The things that actually make a difference that move the needle are things like September 11th, Lehman brothers can't find a buyer, and it causes it to go bankrupt, starts a financial crisis, COVID-19, Pearl Harbor. Those are the things that actually move the needle more than anything else before it. And the common denominator of all those events is that it's not that they were big, it's that they were just surprises that virtually no one saw them coming until they hit. I think that is too uncomfortable an idea for most people to really accept wholeheartedly. It's too painful to think that the biggest risk in my life personally and at the macro level for society is something that I cannot even fathom today but you know it's the case. It's definitely the case, but it's so painful to accept that I think that's why people cling to the forecast, even if making those forecasts is not going to make that much of a difference in their life. | |

| Chris Davis | 03:18 | I love that there's a category in the CIA where they talk about unknown unknowns. That idea of unknown unknowns, the way it should shape investing is really... the best phrase is Howard Marks says where he said you can't predict, you could prepare. Knowing that, you think of the business characteristics that you should be thinking of as an individual investor or the fund characteristic which is that bad things are going to happen or unpredictable things are going to happen, both bad and good. If those unpredictable things are going to happen, what are the characteristics I want in the businesses I own? Then of course, you get the right list. Instead of thinking about what's going to happen, which is unpredictable, you start thinking about things you can know, which is resilience, leverage, durability, competitive position, the past record of adapting and so on, and it reorients the conversation and gets you away from forecasting what is unpredictable and analyzing what is already known. |

| Morgan Housel | 04:19 | The other side of that I would say is that if you are only prepared for the risks that you can envision, then 10 times out of 10, you're going to miss a surprise. And therefore you need to have a level of conservatism and preparedness in your finances that doesn't make sense. If it makes sense, you're missing the surprise, always. I think it always needs to be that you look at your finances and you say, "Look, given my forecast of the year ahead in my career and personally, and the expenses that I think are about to arise, if it all makes sense, given my level of savings, that's when you're vulnerable." It needs to be a level where you're like, "Gosh, I have a lot of cash right now. What am I saving for?" That's when you know you're doing it right, and that's uncomfortable for people. They want to have a level of savings, and cushion and liquidity that makes sense given their view of the world. I think that's why a lot of corporations and whatnot fall for this as well. |

| 05:09 | The banks during the 2000s... if you go back to 2005, 2006, 2007... were repurchasing a lot of stock based off of the idea that they had excess capital. And then 2008 rolled around, and it was like, "No, you actually needed that capital a lot." But in 2006, given their view of the world, it was excess. It was capital that they did not need anymore, so they used it to repurchase shares. Just that having a view of the world that whatever you think it's going to be, adjusting that by 20% or 30% for surprises, I think that's the only way to deal with the world where risk is what you don't see. | |

| Chris Davis | 05:39 | Yeah. And for the advisor, it is trying to anticipate how your client will behave in the face of those surprises. There may be a client that needs that big cash cushion because they're going to panic otherwise, and you may have other clients that feel an enormous amount of resilience about that or they're in 401k plans where it's automatic, they don't check the statements. In which case, you can then have them invest through that period. Knowing that it's unforecastable, the worst thing you can do is feed them forecasts because, yes, they want to know what you think the market is going to do next year but the only honest answer is "I don't know." |

| Morgan Housel | 06:19 | We don't know. |

| Chris Davis | 06:20 | And instead to say, "Well, we don't know but we're prepared both for the fair weather and the positive things that will unfold, but we're also prepared to be resilient and to adapt to those unforeseen disasters." |

| Morgan Housel | 06:34 | The last thing I say here is the difference between an expectation and a forecast. A forecast is if I were to say, hypothetically, the next recession will occur in Q2 of 2023. That's a forecast. But if I were to say, "Historically on average, there are about two recessions per decade, and I expect it to be the case going forward. I don't know when it's going to occur, I don't know what's going to cause it, but at least two recessions per decade is my expectation." Very different from a forecast. But I think holding onto that is just like a baseline expectation of the amount of havoc to experience. Twice per century, there's going to be a major war that upends society. That's an expectation, but I have no clue when it's going to occur or why it's going to occur. |

| Chris Davis | 07:12 | Well, it's like my wife used to say, the secret to a happy marriage is low expectations. I don't know what she meant by it, but anyway, but you're right. Expectations versus forecast, it's a perfect mindset to carry absolutely. |

Chris & Morgan Bios

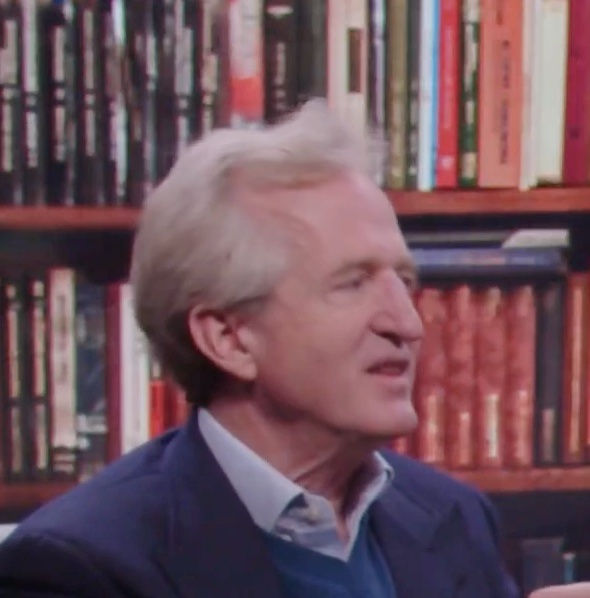

Chris Davis

Chris is Chairman of Davis Advisors, an independent investment management firm founded in 1969 with approximately $26 billion in AUM. As of 9/30/24 He’s co-portfolio manager of the Davis NY Venture Fund as well as other portfolios focused on Large Cap and Financial companies across mutual funds, SMAs and ETFs. Chris has over three decades of experience in investment management and securities research, was recognized as a Morningstar Manager of the Year and sits on the Board of Directors for Berkshire Hathaway.

Morgan Housel

Morgan is a partner at The Collaborative Fund and serves on the board of directors at Markel Corp. His book The Psychology of Money has sold over two million copies and has been translated into 49 languages. He’s won multiple awards and accolades for his writing and insights from the Society of American Business Editors and Writers, the New York Times, and other industry organizations. Morgan has presented at more than 100 conferences in a dozen countries.